Moonrise Kingdom, like Rushmore, the only other film by him that I have seen, I think is a very good film, with a surprising amount of heart. The intentional artificiality of his situations bring to mind classic hollywood filmmaking, particularly those of where stylized narratives were the norm, not the exception. One almost expects Fred and Ginger to waltz into one of the many overly neat rooms. With a few alterations, particularly the language, it make for a nice little Preston Sturges number. However, like Sturges, Anderson's films are able to be identifiable on their own terms, rendering him a filmmaker with enough talent to not only create an unique aesthetic, while continuing to be divisive in how it is presented.

Friday, November 1, 2013

Moonrise Kingdom (2012) and Wes Anderson's aethetic

Intentional quirkiness, thy name is Wes Anderson. Thankfully what spares his works from being to saccharine is the creativity of his methodical art direction and his insanely excellent casting choices. Moonrise is a period piece, though the aesthetic remains the same for his other works. It's a very controlled vision, comparable to Kubrick, making him one of the most auteurist auteurs around. But Kubrick played around with multiple genres, while it seems that "character piece conflict" is Anderson's preferable type of story.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Lili (1953)

It's never a good sign when your "charming" love story could, with a few minor alterations, pass for horror. This is the case for Lili, which pits the distressingly naive Leslie Caron against a quartet of hand puppets that are the residents of the uncanny valley. Why she doesn't flee at first sight of these soulless blinking creations, with their mouths moving like so many nightmare-inducing dummies, is beyond me. It doesn't help that they are controlled by Sir Blandington himself, Mel Ferrer, who continually has this wistful expression that makes it seem like he is staring out longly at a less creepy, more interesting movie nearby. Remember kids, if a guy is continually demeaning towards you, gives you the cold shoulder, and slaps you, it means that he secretly loves you.

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

The Italian Job (1969)

This movie is so unbeliviably cool and groovey, I can't handle it; it's just so wonderfully and enjoyably fluffy, colorful, cartoonish, and really exiting. It's a humorous heist films with one hell of a car chase involving three mini-coopers (each one a color of the Union Jack) that drive around, above and below Turin. It's also so ridiculously British, and patriotic to boot, that one wants to sing "God Save the Queen" by the end. Did I mention that it stars Michael Caine and Noel Coward? Just see it, see it now!

Thursday, June 13, 2013

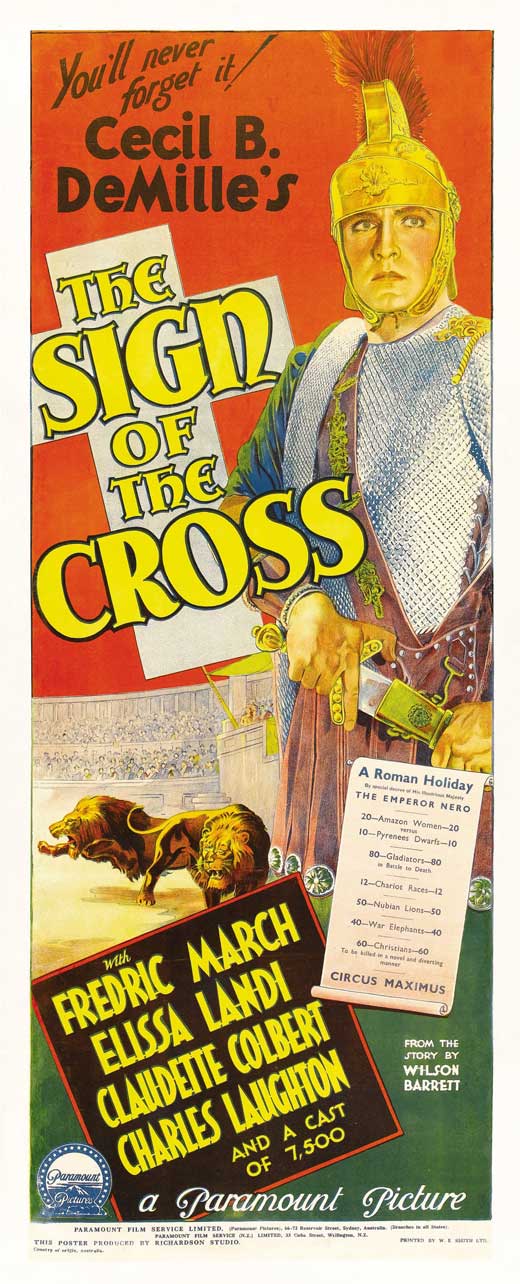

The Sign of the Cross (1932)

via doctormacro

On the one hand, you have the Christians, or Xians if you want to be more extreme. They seem nice enough people, young and old, a bit bellow the poverty line; all they really want to do is hang out together in secret meetings to sing the praises of peace, love, and Jesus. Then along comes the pesky intolerant Romans, who shoot arrows at the worshippers and send them to the colosseum. There, they face being squished by elephants or eaten by crocodiles and lions, in between the acts involving boxing, gladiators and women battling pigmies.

The pagan Roman nobles, which populate this film, by comparison, have it great! Parties all the time, all the grapes one can gobble, with more sexy bisexual prostitutes than you can shake a stick at (all right, you only see one, but there has to more out there in ancient Rome). Add Claudette Colbert (as Nero's horny wife Pomepea) bathing in the milk of donkeys, and you know that they are always having a grand old time.

via doctormacro

Why the film's hero, Prefect Marcus Superbus (Fredric March, looking very superb in a short tunic and perm), should convert in the end and join his pious Xian girlfriend (Elissa Landi) in being lion chow, is a little perplexing. He enjoys having fun with his fellow Romans, enjoying life and not giving a damn what the next day will bring. In comparison to that, the Xians are the ultimate party poopers, preferring to talk of salvation and not partake in more sinful delights.

So After spending more than 2 hours seeing him having a ball chilling with his pagan pals and getting chummy with Colbert, it's a bit of a shock for him to give it all up to convert literally minutes before the fateful gate opens. Then again, in addition to having an admittedly to a cute uplifting final shot, the entire film is supported by lovely decor and costumes, and populated by the always enjoyable March, Colbert, and Laughton, I carry more praise than disinterest towards it.

While I doubt that the film ever succeeded in converting anyone besides Marcus Superbus, it sure as hell provides a good, pre-code, sometimes head-straching entertainment.

Thursday, June 6, 2013

The Eagle and the Hawk (1933)

The early 30's were a good time for World War 1 flix: All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), and Journey's End (1930) showed that war was hell in the trenches, while Hell's Angels (1930), The Dawn Patrol (1930), and today's film take to the air to get their messages across. The latter type of films also had the added bonus of lacking the explicit gore and grungy claustrophobia of it's ground-based counterparts, making sure to intersperse the somber musings with thrilling areal dogfights.

This conflict of interest, to paint a despairing portrait of wartime, while at the same time providing entertainment, figures heavily into the plot of the unfortunately little-known The Eagle and the Hawk. Polo-playing Jerry Young (Fredric March) and working-man Henry Crocker (Cary Grant) are flyboys in France, whose missions consist of taking pictures of enemy areas, and attempting to evade enemy aircraft. While cynical Crocker remains grouchely somber about the whole affair, Young's naive idealism is unable to handle the brutality that surrounds him.

Though he is a talented flyer, he quickly losses a number of tailgunners in a short period of time. When Crocker becomes his newest replacement, the cleft-chins butt heads. But as Grant keeps his head, March slowly breaks from the strain of having his gunners drop like flies. who becomes something of a hero after flying numerous successful missions, slowly breaks from the strain

With a running time that's a little under 70 minutes, there is little time for padding, including romantic liaisons. A glitzy Carole Lombard, drowning in the fur collar of her coat, shows up for about 5 minutes as an understanding woman March meets on leave. She's okay, but it's March and Grant who are really stellar. While the mean-streaks and the hardheadedness of his character may put off some fans, his grudgingly growing mothering devotion to March reveal a more empathetic interior. Heck, I found him to have more chemistry with the leading man than with some of his leading ladies!

March, on the other hand, has a more obviously showy role as the solider growing in depression and desperation. He manages, as usual, to pull it off with great panache, managing to contain his despair enough to function, but not enough to allow him to move onward from his feelings of guilt and inadequacy when it comes to the death of his men. Overtime, however, he is unable to even accomplish that, leading up to a confessional dinner scene that is a bit reminiscent of his drunken.

The strangely affecting bromance between the doomed hero that can barely keep himself together and the forgotten man who's too aware of that is just one of the many moving aspects of this film. The gorgeous cinematography, well-paced story, and great performances from the leads render this to be a near-great ant-war movie.

This conflict of interest, to paint a despairing portrait of wartime, while at the same time providing entertainment, figures heavily into the plot of the unfortunately little-known The Eagle and the Hawk. Polo-playing Jerry Young (Fredric March) and working-man Henry Crocker (Cary Grant) are flyboys in France, whose missions consist of taking pictures of enemy areas, and attempting to evade enemy aircraft. While cynical Crocker remains grouchely somber about the whole affair, Young's naive idealism is unable to handle the brutality that surrounds him.

Though he is a talented flyer, he quickly losses a number of tailgunners in a short period of time. When Crocker becomes his newest replacement, the cleft-chins butt heads. But as Grant keeps his head, March slowly breaks from the strain of having his gunners drop like flies. who becomes something of a hero after flying numerous successful missions, slowly breaks from the strain

With a running time that's a little under 70 minutes, there is little time for padding, including romantic liaisons. A glitzy Carole Lombard, drowning in the fur collar of her coat, shows up for about 5 minutes as an understanding woman March meets on leave. She's okay, but it's March and Grant who are really stellar. While the mean-streaks and the hardheadedness of his character may put off some fans, his grudgingly growing mothering devotion to March reveal a more empathetic interior. Heck, I found him to have more chemistry with the leading man than with some of his leading ladies!

Decieteful VHS cover art: Lombard shares the box with Grant, and with no March in sight, makes it seem that there will be a love story involved (ala Wings or Hell's Angels)

The strangely affecting bromance between the doomed hero that can barely keep himself together and the forgotten man who's too aware of that is just one of the many moving aspects of this film. The gorgeous cinematography, well-paced story, and great performances from the leads render this to be a near-great ant-war movie.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

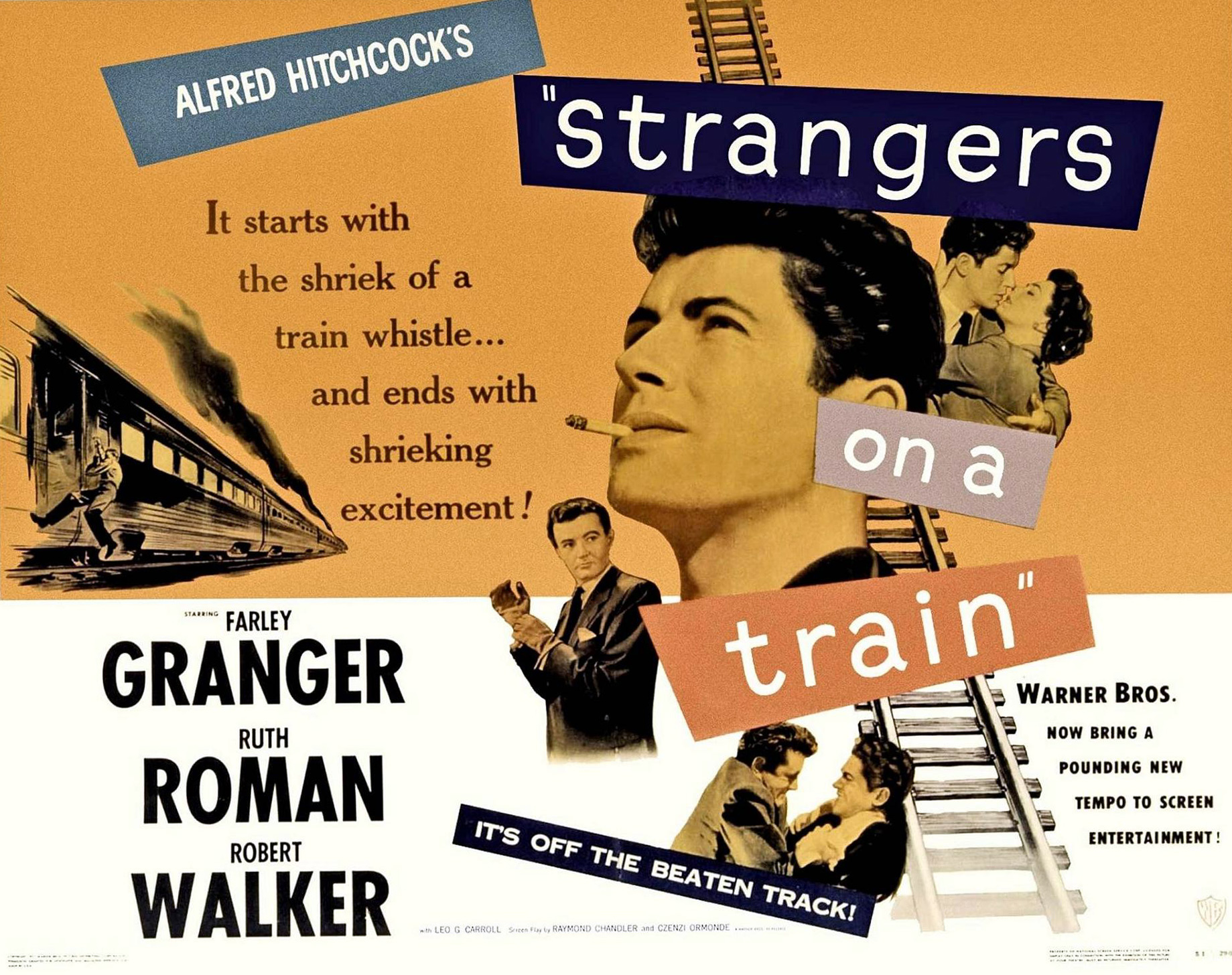

Farley Granger Needs an Escape Plan

I have a theory about Farley Granger movies.

While not one of my favorite actors, this swarthy fellow does have a strange sort of appeal. It might because in the five films that I've seen him in, he plays not-to bright characters that end up getting involved in dirty dealings that are way beyond their control, resulting in exciting hijinks. It might also help that these movies range from okay to Amazing Pieces of Cinematic Art (Senso, Strangers on a Train, and They Live By Night tie for the latter).

But back to my previously stated point: I have a theory to present, and it is this: the serious problems that Granger's characters too often found themselves stuck in could be easily solved if they skipped town and moved to Mexico. I shall support this by using the 5 films I've seen him in as examples.

1. They Live By Night (1948). In this unbelievably gorgeous and sad film, Granger plays an escaped con who, despite the love of his caring girlfriend (the luminous Cathy O'Donnell), is chased to his doom by the law. Partway through the movie, Granger talks of a plan to cross the border into Mexico. However, instead of using his ill-gotten robbery money to find a way to carry this out, he and O'Donnell rent a mountain cabin and give goo-goo eyes to each other on the floor. If only Granger had acted on what he said as soon possible, and skipped town to move to Mexico, he wouldn't have died, and I wouldn't have cried.

2. Rope (1948). In-between 10 minute long takes, Granger and his boyfriend John Dall host a party in their apartment for the friends and relatives of a fellow student, whose strangled corpse is concealed inside a wooden chest that is in full view of everyone. Dall enjoys the situation, while Granger (who did the deed with the rope of the title), gets drunk and breaks under the strain. Now, while I doubt that automatically fleeing the premises after the murder would have allowed him to go scott-free, Granger would at have some sort of chance to escape, and least not have made an ass of himself trying to shot a very disapproving Professor James Stewart; that action could have only added some extra years to his death/and or future prison sentence. At least attempting to skip town and settle in Mexico would have been preferable to that.

3. Side Street (1950). Let loose in NYC, Granger is again married to O'Donnell, this time playing a poor mailman who steals money off some crooks and flees for his life, trying to figure where the money came from while he's doing so. Ignoring the admittedly optimistic ending, our hero does go through plenty of trials (and a pretty sweet car chaise) before he reaches that light at the in end of the tunnel in the last reel. In order to avoid the cops and criminals that jump on his tail, instead of checking into a fleabag motel downtown, he should have kicked up his heels, skipped town, stay in Mexico, and remained there until the heat died down, pregnant wife be damned.

4. Strangers on a Train (1951). If Granger was really sharp, he would have turned down Robert Walker's proposal to exchange murders right away. Heck, as a bonus he could have gotten off that train and took a plane to Mexico! Okay, that would have been a bit much. But even latter in the film, when stalked by Walker in the hope of our "hero" fullfilling his end of the supposed bargain, Granger could have avoided him by skipping town and staying in Mexico for a bit. A final confrontation would have been inevitable, but I doubt that as many lives would be endangered as seen in the movie's ending.

5. Senso (1954). Granger is a real cad in this awesome operatic Italian epic. Long story short, he's a dashing Austrian solider who has an affair with a very clingy and married Alida Valli. When he deserts, he persuades Valli to give him money that would have gone to the very Resistance that he was supposed to be fighting, and to which she is loyal. After getting the dough, does he high-tail it out of the country to live some sort of life in Mexico? Believe it or not, he doesn't! I know that it takes place in the mid-19th century during the Austrian occupation of Italy, but that's no excuse! He just hides out in nearby Venice, and spend the gold on hookers and booze. And what do you know, his girlfriend finds out about it, and she's rather upset about the situation; let's just say that she takes certain actions that make sure Granger pays for his cowardliness.

You would have thought that Farley Granger would have learned his lesson from so many movies, but nope, he has to stay put and allow the plot to go forward. The nerve of him! It makes me so upset that I need to watch something to calm me down...hmmm, I haven't seen Strangers on a Train in while....

Sunday, June 2, 2013

Alvarez Kelly (1966)

I usually have a very good memory when it comes to movies I've watched, especially ones that bring out strong feelings, be they good or bad. I saw this flick about a year ago, and from what I can recollect, it was definitely the latter.

I was in a Richard Widmark phase at the time, and when I found out about the existence of this film, my thought process went approximately like this: Oooo, Richard Widmark WITH AN EYEPATCH! And he battles with William Holden (one of my favorite actors) during the Civil War! And it's directed by Edward "Murder My Sweet, Crossfire, Warlock, The Sniper" Dmytryk. HOW COULD THIS NOT BE AMAZING?!

Alas, I was proved wrong. This film is forgettable; Amazingly, incredibly forgetable. I can recollect what happened, but much of it was so inane, that it's hardly worth repeating. Okay, I lie, it is (no wiki-synopsis-cheating for this recounting):

There's a gang of starving Confederate soldiers, lead by eyepatch Widmark, and they're after a bunch of cows. Holden is a legendary cow-handler, and though he dislikes the mission, Widmark persuades him to help out by shooting off a finger. Oh, and there are a couple of women scattered around, but they're mostly there to prevent the film from transforming into a sausage-fest and illustrate Holden's talent with the ladies, one of whom is Widmark's sexually unsatisfied fiancee, who flees northward with Holden's help, after he gives her some good (fade-out) lovin'.

Remember, this film's plot is hinged on kidnapping cows. Cows. Let that sink in. If you think that it sounds enduringly quirky, think again. With the exception of the previously stated finger-shooting scene (which is admittedly intense), and another where Widmark laughs his ass off non-stop for thirty seconds (which is, admittedly, pretty funny), this was a very listless, workman-like film. Visually and script-wise, there's barely anything eye-catching or even particularly interesting about the affair. It saddens me to imagine the blown potential,what with the eye-patch and all. Oh movies, you never sease to amaze me.

I was in a Richard Widmark phase at the time, and when I found out about the existence of this film, my thought process went approximately like this: Oooo, Richard Widmark WITH AN EYEPATCH! And he battles with William Holden (one of my favorite actors) during the Civil War! And it's directed by Edward "Murder My Sweet, Crossfire, Warlock, The Sniper" Dmytryk. HOW COULD THIS NOT BE AMAZING?!

Alas, I was proved wrong. This film is forgettable; Amazingly, incredibly forgetable. I can recollect what happened, but much of it was so inane, that it's hardly worth repeating. Okay, I lie, it is (no wiki-synopsis-cheating for this recounting):

There's a gang of starving Confederate soldiers, lead by eyepatch Widmark, and they're after a bunch of cows. Holden is a legendary cow-handler, and though he dislikes the mission, Widmark persuades him to help out by shooting off a finger. Oh, and there are a couple of women scattered around, but they're mostly there to prevent the film from transforming into a sausage-fest and illustrate Holden's talent with the ladies, one of whom is Widmark's sexually unsatisfied fiancee, who flees northward with Holden's help, after he gives her some good (fade-out) lovin'.

Remember, this film's plot is hinged on kidnapping cows. Cows. Let that sink in. If you think that it sounds enduringly quirky, think again. With the exception of the previously stated finger-shooting scene (which is admittedly intense), and another where Widmark laughs his ass off non-stop for thirty seconds (which is, admittedly, pretty funny), this was a very listless, workman-like film. Visually and script-wise, there's barely anything eye-catching or even particularly interesting about the affair. It saddens me to imagine the blown potential,what with the eye-patch and all. Oh movies, you never sease to amaze me.

Friday, May 31, 2013

The Killer Inside Me (2009)

Michael Winterbottom's cinematic adaptation of Jim Thompson's novel is a failure because it's too exact; it's too precise and pristine, and too close to the source material.

These issues have and can work for other directors: think Kubrick's overly sanitized and creepy 2001: a Space Odyssey (1968), or John Huston's faithful The Maltese Falcon (1941), which takes most of its dialogue straight from Hammett's book. Keep in mind, however, that these tones fitted with the material given, which is not what I can say about Winterbottom's film.

Thompson's classic pulp story is narrated by its protagonist, a psychopathic homicidal sheriff whose good ol' boy demeanor hides a calculating and mentally unhinged persona. He is a fascinating and frightening character, because we, the reader, are allowed access into his head. But he is telling the story to us, and since he gets less and less control over his impulses as the book goes on, his status as a reliable narrator becomes more shaky until it explodes in our face.

But if there is something that Winterbottom film is, it's reliable. What's presented to us is a accurately designed 1950's Texas town, the characters and most of the events are taken straight from the pen of Thompson. The awful, gross, and explicit bursts of violence are presented in a straightforward manner. Heck, the only real deviation is the sex scenes, which are shown in great detail, instead of the novel's suggested obviousness.

And that's the problem: it's too obvious! Part of what makes the book of The Killer Inside Me so brilliant is how shaky, flakey, and willing the story is to pull the rug out from under your feet. It's comparable to being on a tightrope, and suddenly finding that the net has vanished. Much of the film is shot in close-ups, but in such a way that it reveals only the external, and not the internal. (except for the last shot, which is just plain pretentious). Though it gives itself the air of a deep film about a psycho, it ends up a distant and surprisingly dull piece of celluloid (or digital...whatever format it was shot in).

One more thing: I first heard of The Killer Inside Me the book, from hearing about the hype from the film before it premired. I thought the story sounded interesting, and finding out that this sordid subject was based on a well-regarded pulp novel from 1950 gave me the inciative to find and read that book. And now it's one of my favorite novels. The film, when I finally got around to seeing it, is a simply a big disappointment. If the story still interests you, do yourself a favor: read the book, skip the film.

These issues have and can work for other directors: think Kubrick's overly sanitized and creepy 2001: a Space Odyssey (1968), or John Huston's faithful The Maltese Falcon (1941), which takes most of its dialogue straight from Hammett's book. Keep in mind, however, that these tones fitted with the material given, which is not what I can say about Winterbottom's film.

Thompson's classic pulp story is narrated by its protagonist, a psychopathic homicidal sheriff whose good ol' boy demeanor hides a calculating and mentally unhinged persona. He is a fascinating and frightening character, because we, the reader, are allowed access into his head. But he is telling the story to us, and since he gets less and less control over his impulses as the book goes on, his status as a reliable narrator becomes more shaky until it explodes in our face.

But if there is something that Winterbottom film is, it's reliable. What's presented to us is a accurately designed 1950's Texas town, the characters and most of the events are taken straight from the pen of Thompson. The awful, gross, and explicit bursts of violence are presented in a straightforward manner. Heck, the only real deviation is the sex scenes, which are shown in great detail, instead of the novel's suggested obviousness.

And that's the problem: it's too obvious! Part of what makes the book of The Killer Inside Me so brilliant is how shaky, flakey, and willing the story is to pull the rug out from under your feet. It's comparable to being on a tightrope, and suddenly finding that the net has vanished. Much of the film is shot in close-ups, but in such a way that it reveals only the external, and not the internal. (except for the last shot, which is just plain pretentious). Though it gives itself the air of a deep film about a psycho, it ends up a distant and surprisingly dull piece of celluloid (or digital...whatever format it was shot in).

One more thing: I first heard of The Killer Inside Me the book, from hearing about the hype from the film before it premired. I thought the story sounded interesting, and finding out that this sordid subject was based on a well-regarded pulp novel from 1950 gave me the inciative to find and read that book. And now it's one of my favorite novels. The film, when I finally got around to seeing it, is a simply a big disappointment. If the story still interests you, do yourself a favor: read the book, skip the film.

Saturday, May 25, 2013

The Lady Vanishes (1938)

Lord knows how often I've seen this movie, but this is the first time that I noticed how detailed the train set is. Considering how the majority of the film takes place on it, I guess I must have taken for granted the insane amount of detail that was put into it. Consider the following:

The different rooms shake. That couldn't have been an easy thing to do. Sometimes, it seems that the actors are bouncing up and down, and I admit that next time I see it, it will take up most of my notice. It gives an added vitality and excitement to the scenes.

The moving scenery. Easier to comprehend doing than the previous point, but still effective. The numerous projections of mountains and woods really adds to the flavor of the piece, and serve to remind us of the greater political machinations going on outside the cars.

The lighting. This continued non-stop. The flickering lights on the different faces presented gave us a detail too often overlooked in train-set movies: sign of technology passing by. When the train, and the plot, moves further down the line with the disappearance of Ms. Froy, the lights become non-existant, and a more natural, typically all encompassing lighting takes over, ironically when things get more complicated.

The different rooms shake. That couldn't have been an easy thing to do. Sometimes, it seems that the actors are bouncing up and down, and I admit that next time I see it, it will take up most of my notice. It gives an added vitality and excitement to the scenes.

The moving scenery. Easier to comprehend doing than the previous point, but still effective. The numerous projections of mountains and woods really adds to the flavor of the piece, and serve to remind us of the greater political machinations going on outside the cars.

The lighting. This continued non-stop. The flickering lights on the different faces presented gave us a detail too often overlooked in train-set movies: sign of technology passing by. When the train, and the plot, moves further down the line with the disappearance of Ms. Froy, the lights become non-existant, and a more natural, typically all encompassing lighting takes over, ironically when things get more complicated.

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

The Great Gatsby (1926)

Since the newest cinematic version of F. Scott Fitzgerald will finally be upon us in May, I thought it would be a good time to reminisce about the first attempt to place this classic of American literature on the screen.

Being a fan of the book myself, I must admit to looking forward to the remake with much anticipation. Justing from the trailers, Baz Luhrmann is up to his old over-the-top tricks again. If there is any filmmaker that comes the closest to imitating the old-school borderline kitschy glamour of studio era Hollywood, with modern trappings, this is the guy. It could be bad, it could be great, but it will definitely be an interesting viewing experience.

But what does it have for competition? Why, four other films of course, starting with a silent!

Released four years after the novel was published, it should be the most aesthetically accurate by default, since it was made in the time period that the book was set. And, judging from a contemporary review from The New York Times, it was a rather faithful adaptation, downbeat ending and all. But how well does it translate to film? Do the actors shine? Is it the definitive movie version?

Alas, it looks like we will never known, because this is a lost film. All that remains is a short trailer that incorporates a few brief shots, and from what I can judge, it looks...okay. I feel kinda hesitant to go further than that, considering what little there is to work with, but the scenes appear to be recreated faithfully. I can't say anything about the actors either, except that Warner Baxter looks strange without a mustache in the flashback with daisy.

One thing that can be said in the film's favor is that what little there remains of the party scenes look fun and hectic, with tons of classic bathings suits and much frolicking. The camera is rather static, but then again this is less than a minute's worth of excerpts so maybe there was more enthusiastic cinematography elsewhere.

Some nice on location work, and some copied scenes from the book are are that remain, and that's disappointing. Perhaps there's a script somewhere that gives a better idea of what the film looks like. Until then, we'll have to make due with the little that we have.

Being a fan of the book myself, I must admit to looking forward to the remake with much anticipation. Justing from the trailers, Baz Luhrmann is up to his old over-the-top tricks again. If there is any filmmaker that comes the closest to imitating the old-school borderline kitschy glamour of studio era Hollywood, with modern trappings, this is the guy. It could be bad, it could be great, but it will definitely be an interesting viewing experience.

But what does it have for competition? Why, four other films of course, starting with a silent!

Released four years after the novel was published, it should be the most aesthetically accurate by default, since it was made in the time period that the book was set. And, judging from a contemporary review from The New York Times, it was a rather faithful adaptation, downbeat ending and all. But how well does it translate to film? Do the actors shine? Is it the definitive movie version?

One thing that can be said in the film's favor is that what little there remains of the party scenes look fun and hectic, with tons of classic bathings suits and much frolicking. The camera is rather static, but then again this is less than a minute's worth of excerpts so maybe there was more enthusiastic cinematography elsewhere.

Some nice on location work, and some copied scenes from the book are are that remain, and that's disappointing. Perhaps there's a script somewhere that gives a better idea of what the film looks like. Until then, we'll have to make due with the little that we have.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Her Twelve Men (1954)

You know, this wasn't that bad of a movie. It really wasn't. Sure, I wouldn't go as far to say that it was that good, but it did turn out surprisingly more bearable than I expected. Why? Four reasons:

1. Greer Garson in COLOR. Technicolor to be precise. And boy, does that red hair positively glow. She spends the entire movie actings as a Ms. Chips figure to this young boys in an exclusive private school (though you barely see her teaching anything in a classroom).

But that's beside the point: she looks radiant in color, with green outfits that match some of the walls in the school. Fashion choice, or did no other color go with her hair? We may never know.

2. A puppy. There is an adorable puppy in one scene. The boys try to hide the puppy, but to no avail, because Garson knows, sees, and hears all.

3. One of the students continually practices a tune from Mozart's Don Giovanni, which so happens to be one of my favorite operas. He then plays it with one of the Nazis from Hitchcock's Notorious. This actor, Ivan Triesault, portrayed a dictatorial director in The Bad and the Beautiful (1951). That film also co-stared Barry Sullivan (also as a director), who is in Her Twelve Men as an oil tycoon/concerned parent/Ms. Garson's wannabe love interest. Probably a coincidence, but kinda cool nontheless.

4. Robert Ryan is a good guy. I repeat: Robert "always seems to play a bigot or a crook or a hardass" Ryan plays a genuinely nice, kind, thoughtful science teacher. And he gets the girl, doesn't hurt anyone, and doesn't die to boot! And, surprise surprise, he makes a persuadable nice guy. Forget Lynch or Bunuel: the true face of the surreal is seeing Mr. Ryan strum a guitar around a campfire, surrounded by kids and Ms. Garson, and singing Christmas Carols.

Though I can't say that I would recommend this film to anyone not a fan of Garson or Ryan, I have to confess that I don't regret seeing it. It's a harmless, painless lark, with a few enjoyable perks.

1. Greer Garson in COLOR. Technicolor to be precise. And boy, does that red hair positively glow. She spends the entire movie actings as a Ms. Chips figure to this young boys in an exclusive private school (though you barely see her teaching anything in a classroom).

But that's beside the point: she looks radiant in color, with green outfits that match some of the walls in the school. Fashion choice, or did no other color go with her hair? We may never know.

2. A puppy. There is an adorable puppy in one scene. The boys try to hide the puppy, but to no avail, because Garson knows, sees, and hears all.

3. One of the students continually practices a tune from Mozart's Don Giovanni, which so happens to be one of my favorite operas. He then plays it with one of the Nazis from Hitchcock's Notorious. This actor, Ivan Triesault, portrayed a dictatorial director in The Bad and the Beautiful (1951). That film also co-stared Barry Sullivan (also as a director), who is in Her Twelve Men as an oil tycoon/concerned parent/Ms. Garson's wannabe love interest. Probably a coincidence, but kinda cool nontheless.

4. Robert Ryan is a good guy. I repeat: Robert "always seems to play a bigot or a crook or a hardass" Ryan plays a genuinely nice, kind, thoughtful science teacher. And he gets the girl, doesn't hurt anyone, and doesn't die to boot! And, surprise surprise, he makes a persuadable nice guy. Forget Lynch or Bunuel: the true face of the surreal is seeing Mr. Ryan strum a guitar around a campfire, surrounded by kids and Ms. Garson, and singing Christmas Carols.

Though I can't say that I would recommend this film to anyone not a fan of Garson or Ryan, I have to confess that I don't regret seeing it. It's a harmless, painless lark, with a few enjoyable perks.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

_01.jpg)

_03.jpg)

_01.jpg)